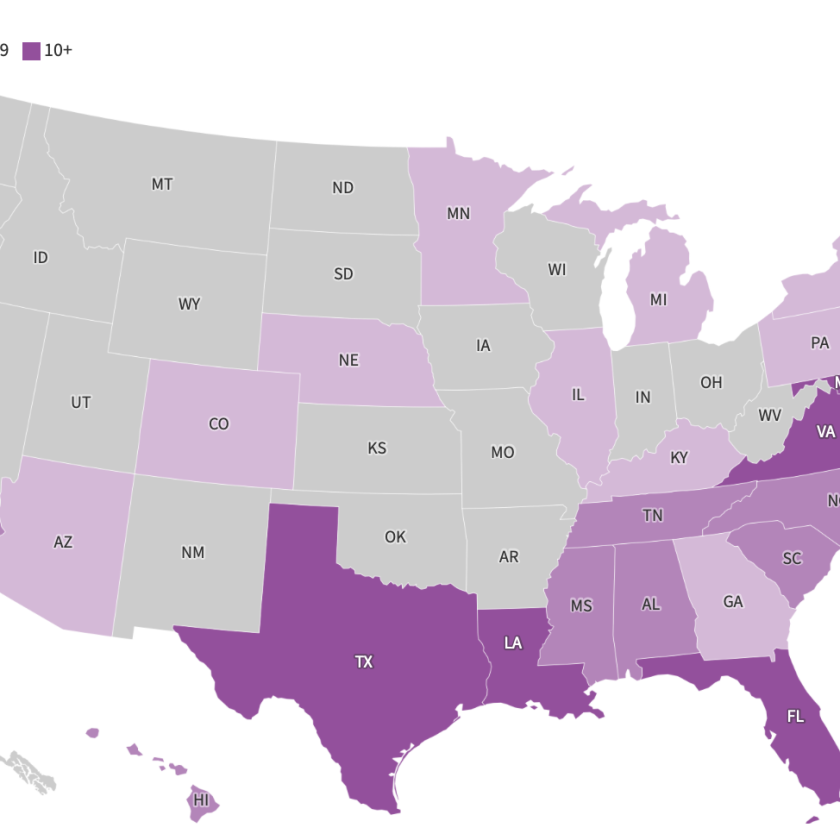

Chronic venous leg ulcers (CVLUs) affect nearly 2.2 million Americans annually, including an estimated 3.6% of people over the age of 65. Given that CVLU risk increases with age, the global incidence is predicted to escalate dramatically because of the growing population of older adults. Annual CVLU treatment-related costs to the U.S. healthcare system alone are upwards of $3.5 billion, which are directly related to long healing times and recurrence rates of over 50%.

CVLUs are not only challenging and costly to treat, but the associated morbidity significantly reduces quality of life. That makes it critical for clinicians to choose evidence-based treatment strategies to achieve maximum healing outcomes and minimize recurrence rates of these common debilitating conditions. These strategies, which include compression therapy, specialized dressings, topical and oral medications, and surgery, are used to reduce edema, facilitate healing, and avert recurrence.

In 2006, the Wound Healing Society (WHS) developed guidelines for treating CVLUs based on human and animal studies; the guidelines were updated in 2015 by an advisory panel of academicians, clinicians, and researchers, all with expertise in wound healing. The guidelines are organized by categories: diagnosis, compression, infection control, wound bed preparation, dressings, surgery, use of adjuvant agents (topical, device, and systemic), and long-term maintenance. Each recommendation is evaluated according to strength of evidence. (See Levels of evidence.)

WHS guidelines provide clinicians with evidence-based treatment recommendations for caring for patients with CVLUs. A summary of the guidelines regarding compression, infection control, wound bed preparation, dressings, and long-term maintenance, is provided in this article. You can access the full guidelines.

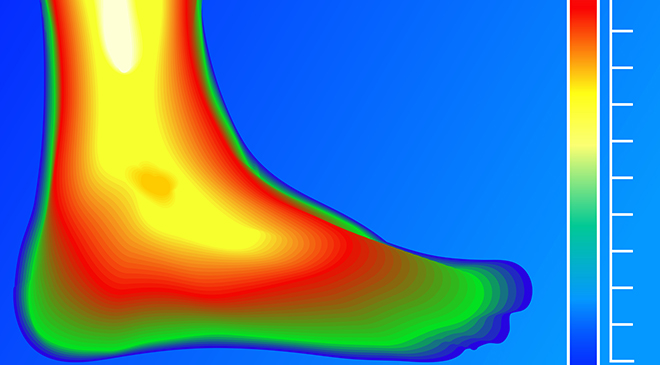

Lower extremity compression

External compression has long been the gold standard for treating venous hypertension and the associated edema and ulcerations of the lower extremities. Level 1 recommendations from WHS state to use:

• a class 3 (most supportive) high-compression system to enhance healing of CVLUs. Methods of compression include multilayered elastic compression, inelastic compression, Unna’s boot, and compression stockings. Consider patient cost and comfort when choosing the method.

• intermittent pneumatic pressure with or without compression dressings to stimulate venous return.

Infection control

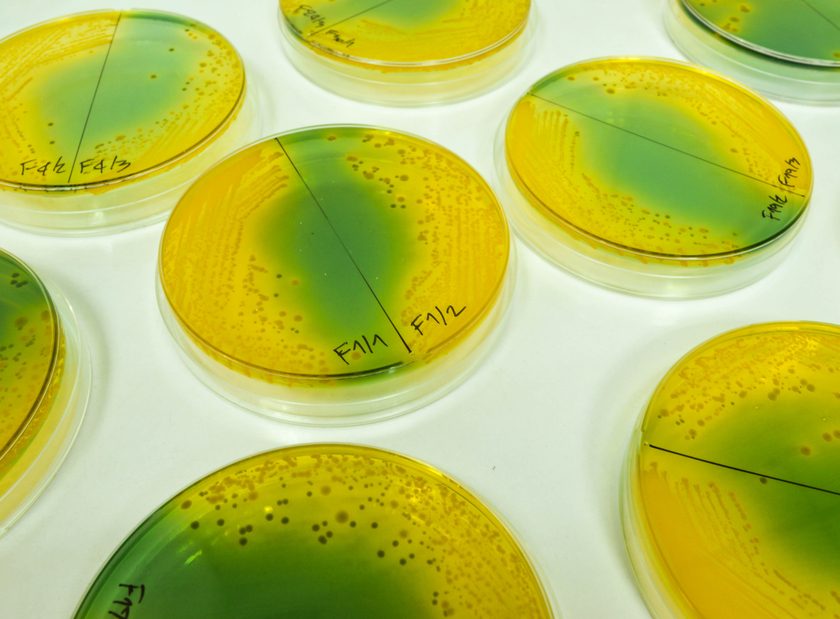

Preventing or treating infections as soon as possible are important because overgrowth of bacteria in the wound bed impedes wound healing. The only level I recommendation from WHS in this category is to debride (using sharp, enzymatic, mechanical, biological, or autolytic methods) necrotic or devitalized tissue that can be a source of bacterial growth.

Level II recommendations:

• Collect a tissue biopsy or use a quantitative swab technique to determine the type and level of infection in the CVLU.

• Prescribe an appropriate topical or systemic antimicrobial therapy based on the findings from tissue biopsy or culture and discontinue the antimicrobial agent when the bacteria is “in balance” (defined as ≤1 x 105 CFU/g of tissue with no beta-hemolytic streptococci) to reduce the chances of cytotoxic effects or bacterial resistance.

• Use systemic gram-positive bactericidal antibiotics to treat cellulitis around the CVLU site.

• Reduce bacteria levels in CVLU tissue before trying surgical closure (≤1 x 105 CFU/g of tissue with no beta-hemolytic streptococci).

Wound bed preparation

Wound bed preparation is used to accelerate healing or to facilitate the effectiveness of other therapeutic measures. To achieve these goals, the level I recommendation from WHS is to document the history, recurrence, characteristics (location, size, exudate, staging, condition of surrounding skin, pain), and healing rate of CVLUs on a regular and ongoing basis to determine if care plans need reassessment.

Level II recommendations:

• Complete a comprehensive history and physical examination to assess for factors that may be contributing to tissue damage. These factors include systemic diseases, medications, nutritional status, and potential causes of inadequate tissue perfusion and oxygenation, such as dehydration and cigarette smoking.

• Perform maintenance debridement to remove cellular debris, necrotic tissue, excessive levels of bacteria, and senescent cells, which will help create an optimal healing environment.

WHS also makes one level III recommendation, which is to cleanse the wound with sterile water or saline initially and at dressing changes to remove debris. Using increased intermittent pressure to deliver the water or saline solution is acceptable.

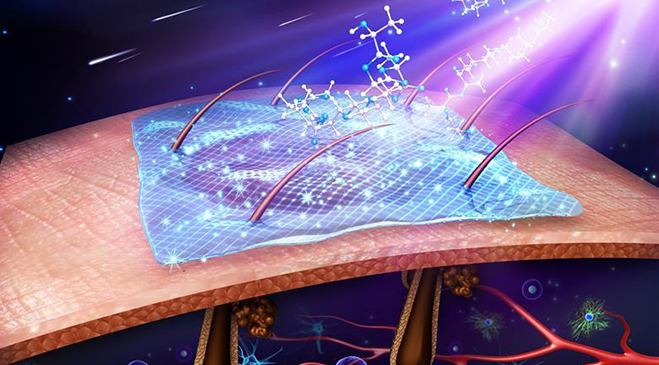

Dressings

WHS recommendations are to consider patient activity, wound location, and peri-wound skin quality when choosing a dressing that:

• sustains a moist wound environment (for example, a continuously moist saline gauze dressing), which promotes cell migration, matrix formation, and debridement and helps reduce CVLUassociated pain.

• diminishes wound exudate and therefore protects skin around the CVLU from maceration.

• is cost effective (factor in clinician time, application time, healing rate, and unit cost).

• remains in place, reduces shear and friction, and does not cause further tissue damage; adhesives are not required when using compression systems. (Note: This is the only level II recommendation; the others are level I.)

Another level I recommendation is to consider using adjuvant therapies (topical, device, or systemic) if there is no healing progression within 3 to 6 weeks of beginning a treatment plan.

Long-term maintenance

CVLUs are considered long-term problems because of their high recurrence rates, so long-term maintenance is required even after ulcers have healed. WHS guidelines for long-term maintenance and prevention of CVLUs state that patients:

• with healed CVLUs should wear compression stockings continually and indefinitely to help reduce venous hypertension— the underlying cause of CVLUs. (Level I recommendation.)

• should perform exercises that increase calf muscle pump function on a regular basis. (Level III recommendation.)

A patient-centered care plan developed by a multidisciplinary team that includes evidence-based treatment strategies for CVLUs will produce the best possible healing outcomes and help prevent recurrences of these recalcitrant wounds.

Jodi McDaniel is an associate professor and director of the Honors Program at The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio.

Selected references

Alavi A, Sibbald RG, Phillips TJ, et al. What’s new: Management of venous leg ulcers: treating venous leg ulcers. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(4):643-64; quiz 665-6.

Ashby RL, Gabe R, Ali S, et al. Clinical and cost-effectiveness of compression hosiery versus compression bandages in treatment of venous leg ulcers (Venous leg Ulcer Study IV, VenUS IV): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383(9920):871-9.

Beidler S, Douillet C, Berndt D, et al. Inflammatory cytokine levels in chronic venous insufficiency ulcer tissue before and after compression therapy. J Vasc Surg. 2009;49(4):1013-20.

Bergan JJ, Pascarella L, Schmid-Schonbein GW. Pathogenesis of primary chronic venous disease: insights from animal models of venous hypertension. J Vasc Surg. 2008;47(1):183-92.

Marola S, Ferrarese A, Solej M, et al. Management of venous ulcers: state of the art. [published online ahead of print June 21, 2016]. Int J Surg. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.06.015.

Marston W, Tang J, Kirsner RS, et al. Wound Healing Society 2015 update on guidelines for venous ulcers. Wound Repair Regen. 2016;24(1):136-44.

Raffetto JD. Dermal pathology, cellular biology, and inflammation in chronic venous disease. Thromb Res. 2009;123(Supplement 4):S66-S71.

Rice JB, Desai U, Cummings AK, et al. Burden of venous leg ulcers in the United States. J Med Econ. 2014;17(5):347-56.